after method: a conversation with hanna reichel

queer grace, conceptual design, and the possibility of theology.

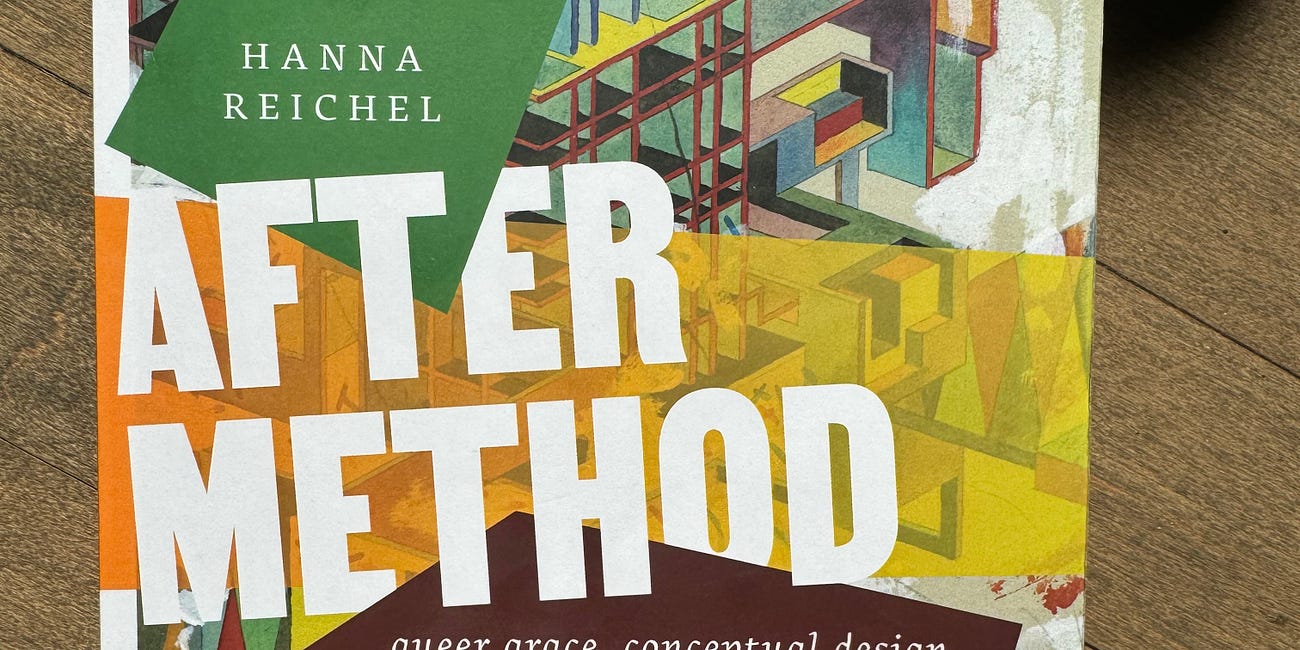

I had the incredible opportunity to talk with Dr. Hanna Reichel earlier this year about their latest book, After Method: Queer Grace, Conceptual Design, and the Possibility of Theology.

It is an intriguing read. After Method assumes the impossibility of doing theology right–and moves beyond it. Leaning on that great Lutheran refrain of “grace alone,” Hanna offers a middle way between either baptizing method as salvific or throwing it out method altogether.

Below you will find several snapshots of our conversation, but I encourage you to listen to the full conversation with an extended introduction in the audio format.

Whether you have already read After Method or just find these topics interesting, I hope you will find this conversation to be both intriguing and thought-provoking.

Listen on Substack | Spotify | Apple Podcasts

Dr. Hanna Reichel is associate professor of reformed theology at Princeton Theological Seminary. Reichel’s teaching spans doctrine and political theology. Their research interests include Christology, theological anthropology, eschatology, doctrine of God, theological epistemology, political theology, queer theology, and theologies of the digital. Reichel has authored two monographs and more than two dozen peer reviewed articles or chapters, as well as co-edited six volumes or themed journal issues. After Method is their second book.

Amar: After Method aims to pave a middle way for theologians to do theology well by utilizing method without falling into two common extremes: either to treat a single method as absolute and sovereign or to assume that all propositions of method are meaningless. As you offer this way of doing theology, you put two theologians in conversation: Karl Barth and Marcella Althaus-Reid. This is of course a really fascinating and unlikely pairing.

I was wondering if you could share more about this task of doing theology well and what method it has to do with this, and why you chose to put these two voices in conversation.

Hanna: Methods are kind of an apologetic enterprise, right? They attempt to establish theology as having something to say to other intellectually rigorous endeavors. And once we pinpoint that right, this is actually something that it can do.

But this also then gives it its particular inflection. It arises out of a dialogue with an interlocutor and attempts to frame what you're going to say. In my case, this is less the idea that, if you just come up with the right method, then you're going to have the uniquely distilled, universally valid truths, and more this idea that you have to be able to communicate what you say in a language that is intelligible to this intellectual interlocutor.

The pairing of Barth and Althaus-Reid is also to slightly catch anyone off guard who might be conversant with one but not the other side; because obviously, they will not arrive at the same conclusion, and they will not come to the same language. (And my attempt is also not to make them say the same thing! That would be ridiculous, they both would be highly uncomfortable with that).

It's rather to open up some space for this—to discover some ways in which they surprisingly rhyme. It is this wager that if they're both—and I think they are—people who are really really seriously trying to think about God and the world, then surely some of the hunches they get from their very different backgrounds would also rhyme.

Amar: I've been thinking more and more about the uplifting of this perfect theological endeavor being flawed from the very beginning because the precondition for this perfection is flawed.

Throughout the book, you're constantly pushing the reader away from this pursuit of perfection that the goal isn't a perfect theology, it's simply a better theology. It's not to develop the singular perfect method, but to find methods and tools that are useful.

So I'm curious how we can continue to do this work of releasing the standard of perfection and simply look towards doing theology better today than we did yesterday.

Hanna: Releasing the standard of perfection is probably an ongoing spiritual struggle, right? That we do all the time and through life.

But maybe the question of releasing the standard should also be a secondary struggle. I wonder whether the thing we should invest our attention and energy is actually this honing and broadening our attention—to listening better by attending to the multiplicity of experiences that we already have in our embodied existence and our social, spiritual, political involvement in the world. And listening to others who may actually not have the same kind of theological language that we do. Then we can ask ourselves more seriously what language can capture those experiences, and what cannot. How do our words and our ideas and our concepts interact with those realities. What do they do to them?

Amar: I think that gets a lot into the latter half of the book where you get into design theory, right?

Hanna: There's one notion that became really central for me from design theory, and that's the notion of affordances. The interesting thing about the affordances is that it is a relational concept.

It teaches us that when we contemplate what an object is for—what it is doing and what it can do—it's actually not something that is intrinsic to the thing itself. It's something that is only established in the relationship and therefore we have to pay attention to who engages in this thing.

In the natural environment, we could say a twig affords sitting for a bird, but not for a bear. But for a bear, it affords eating; for the bird, it doesn't.

I wonder what happens if we think about theological concepts that way.

Amar: I'm in conversation with folks trying to wrestle with these different questions and I’ll ask them what they think of when I say “Christianity” and “goodness.” The overwhelming response is “incompatible.”

They say, “I have to get through so many obstacles before I can put Christianity and goodness in a positive relationship.” This is fascinating to me.

Hanna: Yeah, maybe we are tempted to do this locating work too quickly, too definitively, and too self-assuredly. Precisely in light of the kinds of critiques that you voice, it's not so clear historically, or even in the present and so forth, that, like, Christianity is a benign thing in all its manifestations.

Who are we to say, right? Even Jesus says, “Who are you calling good? No one is good but God alone” (Mark 10:18)

I think there's something in there that doesn't cut off our pursuit of goodness or our curiosity and urge and the ongoing need to find and create more good in this world. But we should do so without being too sure that we know exactly what it looks like and how to achieve it.