beings in Time

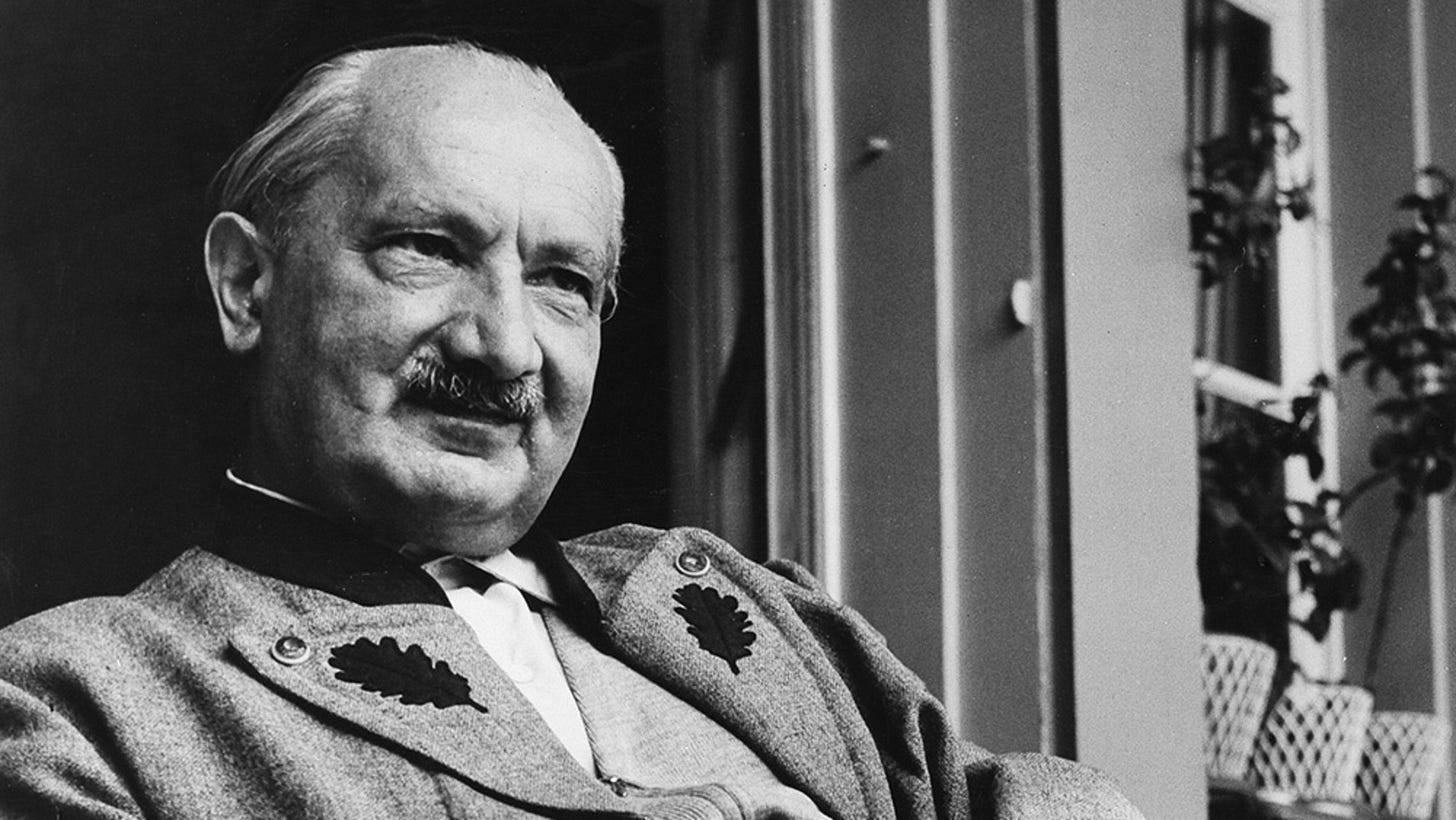

martin heidegger’s clue for how to authentically inhabit time with others

As I jump back on the proverbial horse and begin writing final papers during my PhD course work, I’ll share them here behind a paywall. This is because they are, for the most part, experiments—I am tinkering with thinkers and ideas in a format that promotes such exploration. These essays are also not my typical style of writing for TCL and I don’t imagine most want to read the ~7,500 below on a 20th century German philosopher.

However, for those interested or inclined to read, I’d love to know your thoughts! If you’d like access but cannot purchase a paid subscription, let me know and I’ll make this available to you.

adp

Once one has grasped the finitude of one’s existence, it snatches one back from the endless multiplicity of possibilities which offer themselves as closest to one—those of comfortableness, shirking, and taking things lightly—and brings Dasein into the simplicity of its fate [Schicksals]. – Martin Heidegger, Being and Time.

The perpetuity of being-in-the-world is not that of spectators watching a show from the stalls. Consciousness is not an abstract receptivity divorced from memory and acquired habit. - Jean-Yves Lacoste, The Appearing of God.

“The question is not whether we know what is coming, but how we live in the light of such expectation.” - James K.A. Smith, How to Inhabit Time.

—

What precisely is the kind of being that would interrogate the very nature of its Being? Moreover, how does such a being, which only exists within the conditions of its Being-in-the-world, step outside of itself to interrogate this nature? Can this being ever interpret itself in this reflective light? Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time provides a monumental shift in how we approach and address the question of the meaning of Being. In contrast to commonly held propositions of the self that followed Aristotle in conceiving of Being in terms of substance (ousia) and Descartes’ cogito sum, Heidegger ultimately demonstrates a deep, inseparable entanglement between human beings and the world.[1] Said another way, Heidegger’s existential analytic of Dasein reverses Descartes’ conception of “I think, I am” by treating the latter statement as the starting point. In doing so, Heidegger rejects the categorization (or status) of the cogito as a point of departure.[2]Priority is given to existentia (existence) over essentia (essence). As Heidegger explains, “within-the-world-ness is based upon the phenomenon of the world, which, for its part, as an essential item in the structure of Being-in-the-world, belongs to the basic constitution of Dasein.”[3]

Nearly a century after the publication of Being and Time, we still too often think of ourselves as standing outside and over the world—above and beyond time—observing it as outside actors unaffected by the tossing waves of possibility and the reality of our ultimate impossibility.[4] This failure to consider our temporality is to forfeit the task of uncovering the meaning of Being. It is, in a way, to forfeit our humanity, to be something less than Dasein—less than the kind of beings who would inquire about the Being of beings. This makes a recognition of our temporality and finitude of the utmost importance. Therefore, in this essay I explore how Heidegger throws us back into time—into the very phenomenon of our Being-in-the-world. Dasein itself temporalizes and therefore time becomes the condition for our own self-awareness. Said another way, temporality (Zeitlichkeit) is the condition for the possibility of understanding the meaning of Being. Through Dasein’s structure of primordial temporality, we are clued into both the freedom and anxiety that accompany our existence. The “existential circulation” of Dasein’s unity and finite structure in its futurity, fallenness, and being-alongside constitute what it means to exist in a constant distention as beings in time.[5]

To advance this task, this essay will first interrogate the inauthenticity of average everydayness demonstrated in what philosopher James K. A. Smith calls the delusion of “nowhen” and the condition of “spiritual dyschronometria.”[6]The pervasive whispers of the “they” (das Man) assure us that we remain unburdened and unaffected by the conditions of our temporality and thrownness and free to choose as we wish. Yet, this temporal dislocation envelops us in the “they” and its moods of curiosity, ambiguity, and idle talk. Subsumed within the “they,” we are dissolved “completely into the kind of Being of ‘the Others’, in such a way, indeed, that the Others, as distinguishable and explicit, vanish more and more.”[7] The freedom promised in the “nowhen” is little more than radical un-freedom of being trapped in the bland inauthenticity of the “they.”

Following Heidegger, I will turn to the feeling of the uncanny (Unheimlich)—an awareness of things once taken for granted, a discomforting sense of estrangement with one’s understanding of the world—as a way out of the “they.” But the thrown possibilities of individuality uncovered apart from the “they” most certainly lead to anxiety. This anxiety concerns the nothingness of our freedom—that there is nothing which must be and yet, in guilt, “I am.”[8] Ultimately, it is anxiety that accompanies the “possibility of our impossibility.”[9] Rather than retreating back into the inauthentic “they,” Heidegger’s solution to this anxiety is not in trivial attempts to stave off our inevitable conclusion, but, in hearing the authentic “call”, to resolutely anticipate—to come face to face—with our finite condition of being-towards-death and, in doing so, be freed from the “they” and into an authentic way of Being-in-the-world and Being-with-others.

Finally, I will take the emphasis on care and anticipatory resoluteness in Being and Time as a model for a life shaped by futurity. This Heideggerian futurity is not beyond or removed from being-present but rather is the very condition of it. “Only so far as it is futural can Dasein be authentically as having been. The character of “having been” arises, in a certain way, from the future.”[10] In this we see Dasein’s existential circulation—a forward and backward loop of futural projection and already-having-been—as a model of authenticity. Arguing that Heidegger clues us into how to be the kind of beings who inhabit time, I briefly conclude, perhaps despite Heidegger’s best efforts, that this futural orientation can be a deep source of hope for the religious reader.[11]