earth filled with heaven: a conversation with fr. aaron damiani

have our imaginations been baptized like st. patrick or warped like saruman?

I found my way into Immanuel Anglican Church during a low season of life. I was pushing my way through another semester of undergrad, dealing with the beginnings of deep anxiety, struggling to hold my closest relationships together, and desperately attempting to get out of a destructive living situation.

The church Emily and I had attended for over a year was only making matters worse. The performative worship, the unsound sermons, and the spiritual abuse accomplished in the name of the Spirit all infuriated me. For all the Sundays we spent there, I never once talked to someone on staff. I felt unknown, unloved, and unseen.

So, when Emily was away for one weekend, I jumped on the CTA Red Line like every other Sunday, but took the train two stops farther than normal to the Wilson station and walked through Uptown to Uplift High School.

I didn’t know what to expect. I had never heard of “Anglicanism” before. I heard there was a “liturgy,” that everyone called the lead pastor “father,” and that the congregants there genuinely loved Jesus. It was enough to get me in the door.

I walked in expecting to fade into the background. Yet, as soon as I found a seat a mew staff member tapped me on the shoulder and kindly introduced themselves. Soon after, Fr. Aaron slowly began making his way around the sanctuary to say hello to those seated early. I waited patiently, not sure if I was ready to meet a father. I kept my head down looking through a bulletin filled with language I’d never heard before.

But when Fr. Aaron came over to say hello, I was met with the presence of the Holy Spirit at work in the life of a faithful servant. Our conversation was brief and uneventful. But it stayed with me throughout the service and the remainder of the week, and month. For years, we journeyed with Immanuel Anglican through the liturgical season, singing, celebrating, fasting, and worshiping along the way.

The kindness and hospitality that Immanuel showed Emily and me in our years there have shaped me deeply as a Christian in ways words could never fully express.

This summer Fr. Aaron was kind enough to send me an early copy of his latest book. After reading it, I was eager to talk to him more about all he had written. Below you will find our conversation that covers topics including joy, spiritual motherhood, creation care, Tom Bombadil and the Lord of the Rings, and, of course, living a faithful, sacramental life.

AARON DAMIANI (MA, Biblical Exegesis) serves as the lead pastor of Immanuel Anglican Church in Chicago and is the author of The Good of Giving Up: Discovering the Freedom of Lent and Earth Filled with Heaven: Finding Life in Liturgy, Sacraments and other Ancient Practices of the Church. Aaron writes and speaks regularly about spiritual formation, leadership, and recovering the gifts of the ancient church for today's challenges. Aaron and his wife Laura live with their four kids in Chicago's Irving Park neighborhood.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Amar: I have sensed—and you name it in the book—a skepticism around the idea of liturgy. The common critique is that it is like a plug-and-play or pre-programed church system.

There's been a lot of answers to this critique, but you make an interesting move that I haven't read or seen anywhere else. You write, “Whatever the celebration, liturgy does not compete with joy. In most cases, liturgy clarifies the joy. Liturgy helps us channel our joy. Joy and liturgy go together like a bride and groom” (100). I think this is so spot-on. Could share a bit more about this relationship?

Aaron: So, right off the bat, I want to give props to Peter Leithart, who has a great chapter on joy in his book on liturgy. Theologically speaking, it's, it's a piece of art.

I think from my perspective, my writing on liturgy and joy does come from my experience of liturgy that did two things. Number one, it gave some of the darker emotions that I had—some of the minor key emotions like sadness, fear anger, and grief—it gave me a way to express that and to process that in the presence of God. This came especially through silence and the psalms and confession. That gave me the capacity to express more joy, even when I didn't feel like it.

And so, there was one moment—I think a turning point moment for me, Amar, was when I was a skeptical graduate student at an Easter vigil, my first ever Easter vigil. And I write about this a bit in The Good of Giving Up. But I tell the story a lot because it was a turning point in my life.

I showed up to a joyful worship of the resurrection of Jesus Christ—the most joyful possible—and what that did is bring all my skepticism to the surface. And this wasn't necessarily good faith skepticism. Some of it was hardness of heart and intellectually dressed-up pride and which was keeping me from that childlike “second naivety” of just entering into the transfigured delight of the worship of Jesus Christ.

And so, what happened was that in the middle of that service, during the Readings and the Songs in the first part of the Vigil of Light, people were wholeheartedly worshiping. And I was looking with contempt, some sadness and longing around me feeling like I couldn't get there. I couldn't enter that level of worship. I was like in an astronaut suit, cut off from the air they were breathing and floating above, separate from this celebration, this worship.

I was put off by the joy, quite frankly. I didn't like the liturgical joy. But what happened was in the middle of that worship service is that the new members and baptismal candidates—since the earliest days of the church—were welcomed on the Easter vigil. I was becoming a new member and so I had on one of those white robes and a pastor was praying for me, and he just spent a moment in silence before he prayed over and anointed me with oil. And he said, “Aaron, I don't know if you're wrestling with doubt right now, but I want to ask that the Lord would help you and give you some freedom from doubt.” That's about all he prayed.

And then he anointed me with oil in the name of the Father, Son, and Spirit, and I experienced what was—I look back on now—a moment of the Lord Jesus setting me free through the Holy Spirit. And what happened then was I was able to enter into a new level of joy that was previously unknown to me.

And the best way I knew how to describe it was in this context of liturgical worship service where upbeat songs as well as ancient liturgical forms were both present. Both helped me express what my heart most wanted to say.

And so, I have found since that the joyful exercise of liturgy actually channels joy, it clarifies joy, it strengthens joy. I may not always feel joyful, but the liturgical forms of the church—if expressed with that openness to the Holy Spirit—is going to tap into what we humans are capable of when we come into the presence of God.

Amar: You talk about the moment when you in began to see the church as Mother where you were not a “customer to be managed” but a “son to be loved” (18). Could you briefly share what this moment was - and then expound upon this mothering role of the church?

Aaron: Yes, I remember that moment. I was a Moody [Bible Institute] upperclassman, and I was excited by my first megachurch experience. There was a novelty to being part of something that was big and growing, where for the most part, your presence was noticed once you filled out the communication card for the first time; but, then your presence went unnoticed when you stopped filling out the communication card.

Andy Crouch talks about how much of what it means to be human—knowledge work, family, money, embodiment—is disconnected from relationships. And I think that in modernity this is all over the place. We are more catered toward, but we are less known. It’s a personalized worship service without any personal connection required.

When I entered a smaller liturgical church, I was in bad shape. I was emotionally burned out from a season of grieving and loss. I was intellectually burned out from doubting my faith. My theological underpinnings were being questioned and scrutinized and I didn't know what to believe. On top of that, I was burned out from overextending myself in my first leadership assignment. All told, I couldn't think my way to God, feel my way to God or lead and minister my way to God anymore. Yet I longed for God.

And Covenant - the church I visited - made a space for me. I've learned about the Benedictines and the way that they practice hospitality. They treat guests as they as if they were Christ himself; and you just can stay with them and they take care of you. And so, there was some—although they didn't call it this—Benedictine hospitality for me at Covenant. I could come and be a part of the community, partake in the liturgical forms, partake in the life of the church. I could receive the creeds, receive the sacraments, receive the community. And my soul could rest.

There wasn't an expectation for me to lead. There wasn't an expectation for me to give a demonstrably emotional expression of worship to make the worship service seem more impactful. There were no performative worship expectations of me. Not having that pressure was really good for my heart and soul.

The mother analogy I think fits because the church was there to give, not to take and that’s what mothers do. They notice their kids when they're discouraged or when they don't have a lot to give, and they are ready to bring that nurture, that comfort, and those open arms to receive someone as a guest and receive someone as a child. Mothers do this without patronizing, and without coddling and controlling. This church was simply making space for hospitality, both in liturgical and non-liturgical ways.

There's something feminine about the church. The gifts that She imparts are done so in a very motherly way. It's a beautiful mystery. And it was a healing thing for me.

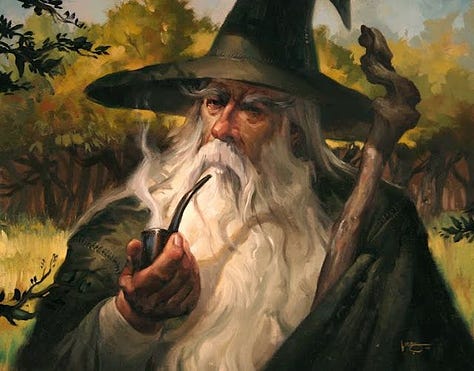

Amar: You ask this wonderful question in the book. You write, “This is the fundamental issue around our view of the world: Can we see Jesus Christ in creation, around creation, and through creation? Have our imaginations been baptized like St. Patrick’s or warped like Saruman’s?” And so, I want to ask this question of you. Could you describe these two ways of being — of Saruman and Saint Patrick — and how we can follow the latter in bearing witness to Jesus Christ in, around, and through creation.

Aaron: Well, right now, this is a very important question because as Christians we do affirm that God created the world, and we also are aware that he will recreate the world. What is important is how we treat creation in between.

The Evangelical temptation has been to denigrate creation because we know that it has an expiration date and that the Fall has brought a level of curse and a brokenness to the created order. I think what we have been cooperating with unknowingly is modernity’s way of extracting profit and pleasure from creation without any consequences or reverence for creation.

The Christian view of the Fall and the modern view of creation have formed a very ugly stepchild in the way Western Christians have, have regarded creation.

When you look at Saruman, you see somebody who is quite willing to exploit people, creatures, and the creation for his own profit and power and pleasure You can contrast this with Gandalf, who is willing to see the inherent worth and the personhood of the Hobbits that everyone else is overlooked. He treats everybody that he encounters as having a moral end in themselves—not someone who can serve his ends. He is able to extract the goodness of creation, whether in food or in the power of his staff, without being exploitative.

The reason I like St. Patrick's story is that I think that for us, seeing Christ in, around, and through creation begins with recognizing the image-bearing quality of our neighbor. St. Patrick was able to do that even in the eyes of his enemies. And so, if we can love our neighbor, if we can learn to forgive our enemy and bless them, that means that we are going see Christ in, around, and through them. I think this is the starting place. And if we can do that, then we will become empathic when we consider environmental and economic policy that impacts people who live in different countries, or how much we consume.

There is a crucial sacramental element to this. What happens in the Eucharist is that disembodied voices—every way that modernity has separated us from our neighbor, from our bodies, and from the Lord Jesus—those things have to give way towards the incarnate reality of Jesus as made present in the body of Christ and in the Eucharist. And this is a really important corrective for us because when we see that Christ himself is honoring us by being present to us, honoring our neighbor, and being present to them, as well as remembering the incarnation when we come to the Eucharist, God is going to bring us into a more humble, tangible, incarnate connection with Christ and with our neighbor. It is hard to dishonor the image of God when you can see the whites of people's eyes and you're chewing and swallowing right next to them in the presence of Christ.

Amar: The last question I have for you goes back to a story you cite often not only in this book but in your sermons and lectures—The Lord of the Rings. My question is: if you were dropped into this long story, where would you be placed and who would you be?

Aaron: Okay. Yeah, I have thought about this and I'm going to give you two scenarios.

So, my first scenario is that I'm one of the Hobbits dancing on the table at the Green Dragon singing a silly song in way over my head. I would place myself around the time of the trilogy. That's one possible answer that speaks to the part of me that is more creative, lighthearted, loves to be with my friends and, and yet signed up for something that I didn't see coming.

From my perspective now that I'm middle age and getting a little, I'd maybe put myself in like a Tom Bombadil character because he's at a point where he is watching out for people. He’s still creative—he is singing and working with nature and he has a household to run. And, you know, when the hobbits get stuck, he's able to help them get unstuck. He provides them love, hospitality, and some perspective. I think that I might be more of a Tom Bombadil at this point leaning into, leaning into this season where I’ve taken a lot of risks already, and so now what I'm doing is now blessing the next generation. I am looking out for the next generation— trying to give them hope, writing a few things along the way, singing and preaching. But really, now it is about seeding those who are on the journey to push back the darkness and see the light breakthrough.

👏🏽👏🏽