I met Rev. Dr. Erin Raffety my very first day of classes at Princeton Seminary. Although her course, “Theological Foundations for Youth Ministry,” was outside my academic interests, it quickly became a delightful gift in a semester of adapting to a new place and community. It was at a gathering at Erin’s house that I first met her daughter Lucia, who is a beacon of light. Lucia, to whom this book is dedicated, lives with several disabilities and a progressive, terminal genetic disease of the brain—all of which limit her ability to speak, walk, and move purposefully.

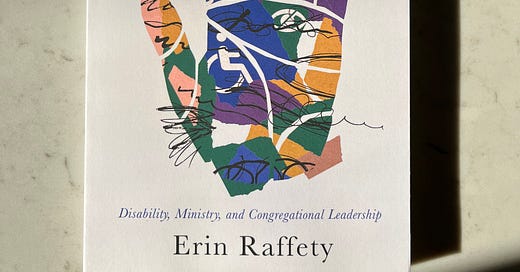

In the following conversation, Dr. Raffety and I talk about her new book, From Inclusion to Justice: Disability, Ministry, and Congregational Leadership (Baylor University Press, 2022). We talk about Lucia, as well as our (collective) failure to imagine what it might look like to have persons with disability leading our congregations. In return, I share a bit of my own experience with disability. Together, we question how our social expectations of normalcy hinder our ability to envision a common good. Finally, we return to Lucia and discuss a way of being in the world centered on giving and receiving love.

Rev. Dr. Raffety is a cultural anthropologist, a Presbyterian pastor, and an ethnographic researcher who has studied foster families in China, Christian congregations in the United States, and people with disabilities around the world. Dr. Raffety teaches and researches at Princeton Theological Seminary, Princeton University, and the Center of Theological Inquiry.

Amar: In the book, you make several key arguments. But one of the primary arguments that I saw woven throughout the book is that in our ministry (with disabled people and ministry in general) there is a value of the able-bodied human experience over what you call the “Christ-centered human experience” that really forms how we do ministry and conceive of the church as a worshiping body. This is a really big topic and a large endeavor to complete the research for this. I'm curious what in your ministry and in your life compelled you to take on this project and then write this text?

Erin: You're right. That is a really big claim and one I wrestled with a lot because at the heart of this book is a concern with pervasive ableism in both society and the church. And you know, you call the church to account for that and I worry people aren't going to like me very much. [Laughs]. But the reason I wrote this book was for at least two reasons:

One is my own experience as a parent of a child with multiple disabilities. As I was pastoring and raising my daughter, we were learning more about her experience as a disabled person. As I was a pastor and kind of receiving all these comments and questions from people in the congregation and struggled with my own experience of ableism and kind of having something like a mirror raised up to me. And then also that mirror—I don't know if the metaphor works—but is also kind of reflecting in a way that I'm seeing the church differently because I'm starting to see the church through my daughter's experience. And despite a lot of good intentions and well-meaning ministry, the practical fact was that she just couldn't access a lot of what was going on in the church and a lot of the attitudes that people had toward her were influenced by this able-bodied culture. I didn't feel like we were really seeing her as God sees her—and I wanted more. That's one kind of personal motivation.

The other motivation is the research. Like, I had to write this book because this is what the research told me to write. As an anthropologist, my deepest desire—and I would also say as a pastor—is to listen well to people and to really appreciate what they say and do, and to trust that God is active in the world and that we can learn from them. A lot of what I was seeing is that even these churches that had robust disability ministries, they were saying, “this is really hard.” And you know, sometimes we feel like we're not getting anywhere. Even more, churches that weren't doing a lot of disability ministry didn't even really know where to start.

And one of the common denominators that I discovered in the research between those churches—and we worked with eleven different churches, and each of those churches had disabled people that were either congregants or leaders in the churches—was that they were all operating through this model of disability ministry that was inclusive.

So, in the book, instead of beating up on people in churches (because you know, how is that helpful?) I beat up on this model of inclusion because I think that it is not serving us very well. And I think that it's not our fault.

I talk in the book about how inclusion is at the heart of how we do education and healthcare and the Americans with Disabilities Act. It's all about accommodations and inclusion. But ultimately, I think that Jesus has a much more profound vision for justice for disabled people, and we're missing that because we're settling for inclusion. And so “inclusion” is doing this undermining thing where it just keeps storing up power in the hands of able-bodied people and institutions. It works against itself, against its goals to include disabled people. And so, I try to show examples of that throughout the book.

Ultimately, I think that Jesus has a much more profound vision for justice for disabled people, and we're missing that because we're settling for inclusion.

And I guess the other reason is my students—like you were one of my students.

The students show up a lot in this book because I was writing this book as I was teaching these classes, you know, on ministry to people with disabilities. And I had all these amazing disabled students in my class. And then I had all these amazing disabled leaders in the church that I was doing ministry with.

God wants us to tell those stories. That was really the third reason. Seeing, despite the sin of ableism and despite all these ways that unfortunately we in our churches fall short, God is still working right through disabled leaders. And the Holy Spirit really is, I think, transforming even our ideas about what it means to do ministry and our ideas about who can, should, would, and could be leaders—and that is awesome. I was really humbled and excited to be able to tell that story. So like as much as the book is really critical, I also hope that it is…I hope that it's hopeful.

A: I think all of those reasons you mentioned are very evident and present in the book. I'm curious, one of the things that drew my attention to this particular text (along with the topic) was this language of “from inclusion to justice.” I think in our world and in the church, if someone were to see the book and it was just titled “Disability and Inclusion” or something like that, they’d say “Oh, yes. Great. We've accomplished justice.”

I think this speaks, obviously, to the way we equate inclusion with justice. Like, we get the feature in the big magazine, we have a seat at the table, we're on the panel next to all of these other minoritized people. The thought is, “haven't we achieved justice because disabled persons are included in these things?” But you push further and say “No, the progression is from inclusion to justice”—we haven’t achieved a moment of justice simply by including disabled people in these conversations.

I'm curious to hear more of your thoughts on this. What is your thinking behind this progression?

E: Yeah, I mean, the core text in the book is this passage about Bartimaeus (Mark 10:46-52). I talk a lot in the book about how I see this story as a movement towards something that looks a little bit more robust, a little bit more like justice rather than just inclusion. (Although, I see all this ableism too in that text and all these problems). That's one of the reasons that I was so drawn to that text.

And then I was also drawn to that text by our informants in this research—the disabled leaders that we were working with. They all really wanted us to use their names to uplift their ministries. So that's something we were able to do—we could go back and ask their consent and put a bunch of people's names in the book. Because, if we were going to amplify their ministry, how could we do it right if they remain unnamed?

The core text in the book is this passage about Bartimaeus (Mark 10:46-52)

And so that's a problem, you know, in the Bible. A lot of these amazing disabled leaders remain unnamed. But Bartimaeus is one disabled person in the gospels who is named and is called into ministry by Jesus. So, one of the things that I think about around inclusion and it not being enough is the way that disability theology has really developed these robust understandings of every human.

The appeal to every human being as made in the image of God is really focused on kind of that aspect of what it means to be inclusive. But that really doesn't do anything to tear down the problems around power and who is in charge and who holds power and how we treat each other. And so what I loved about this Bartimaeus text is that in this passage we see Jesus calling Bartimaeus into ministry.

Because at the end of the passage, Jesus asks Bartimaeus, “what do you want me to do for you?” He sees that Bartimaeus is blind—but he asks anyway. I mean, that move is just so dignifying in terms of really having a conversation with someone about their experience of disability, right? This is something that I talk a lot about: listening and the role that that plays in the church.

In the book, I wanted to really make sure that we move beyond just thinking about disabled people being made in the image of God and recognize that all of the ministry that Jesus is doing not just to disabled people, but calling disabled people into ministry—to actually being ministers themselves. And that's what I think happens in the Bartimaeus passage when Jesus ultimately calls Bartimaeus to follow on the Way.

I feel like sometimes we focus so much on how crappy the crowds are or how amazing the miracle is that we miss the actual climax of the text: that Jesus calls Bartimaeus into ministry and Bartimaeus follows Jesus on the Way.

And so what this says to me is that not only is Bartimaeus a minister in his own right, but he's a leader and someone that ultimately people were going to be looking toward in terms of leading the church. Those are the roles that I kind of try to develop a bit more through the ethnographic research in my book around ministry and leadership of disabled people.

Because, as I said, I think that even in theology we've sort of stopped short at, “Oh, you know, disabled people are made in the image of God.” Well, yeah. Everybody's made in the image of God. Let's talk about ministry and leadership and what this practically looks like. And I think for the church, it's all about how can we receive this ministry and leadership that is absolutely there.

I think that's where I write the book primarily as a person who is able-bodied to other able-bodied Christians. Because if there's no reception, you know, how can the church be ministered to and led in a different way? It's a very kind of humbling role, I guess, for the church to have to take. But I feel like because we've so often made disabled people into problems, there's such an opportunity here in terms of being able to receive ministry and leadership.

So those are, those are sort of some of the pieces when I think about why inclusion isn't good enough and then what justice looks like. And I just think about a world in which we have disabled people not merely being ministered to but ministering to people in the pews. I just think about what that would look like and how that would change us as Christians. And then I think about the disabled leaders in this book. You know, I think about blowing up the whole paradigm of Christian leadership that we have in the church. And I think this leads us in a really faithful direction towards a more collaborative, flexible, caring form of leadership that is going to make us a better church.

A: I think it was in a course at Princeton Seminary that I was taking with Dr. Eric Barreto when guest lectured on this Bartimaeus story. I remember you pointing out what you just mentioned—that Jesus asks Bartimaeus, “what do you want?”

The obvious answer is, “Oh, Bartimaeus wants to be healed.” But I think you’re right in pointing out the dignity that gives to Bartimaeus. Your lecture was part of what inspired me to write a piece in Sojourners titled something like “My Disabled Body Proclaims the Gospel.”

It was also rooted in my experience of people just assuming what was best for me. It was not-so-subtly masking this understanding of disability as an inconvenience. It’s like, “let me try to heal you,” because your disability is a hindrance to or a negative example of whatever Christian practice it's supposed to look like. The assumption is that there are not supposed to be disabled people in the church because if people aren’t healed, then God's not powerful enough to heal.

And so, for me, what was liberating was recognizing sometime in undergrad—as so many eager Bible college students were asking if they could heal me every single day—was the ability to say like, “No, I'm okay. I see my imperfect body as a location from which God proclaims God's self to the world, and that's done through my disability, not in spite of it.”

If God wills for me to be healed at some point, that’s wonderful. But if not, then despite the challenges of disability, God is still present and the gospel is being proclaimed in both word and deed.

I also think about, as you were saying, what would it look like for disabled persons to lead able-bodied people in ministry. It completely disrupts a social imagination of what power is supposed to look like in our society and what has, of course, been mapped onto the church.

You highlight this way of imagining the world as able-bodied people and what that would look like in reverse. And so really I'm wondering how social imagination of normalcy and disability are intertwined in our interrogation of the common good?

Friends, this conversation only continued to get better. To read the second half of this post, please subscribe to the newsletter. To learn more about why I’ve moved to a paid subscription model, read last week’s newsletter here.

…

Hey! If you are reading this, you are a paid subscriber! Thank you, sincerely, for subscribing and supporting this newsletter and the entire “This Common Life” project. I hope you enjoy the remainder of the conversation below.

E: That was a big question, but I do think one of the reasons I go to Twitter in the middle of the book is because I feel like there's all this prophetic work happening among disability activists on Twitter.

And I felt like it was really happening during the Covid Pandemic because people who live with disability, they don't have a choice whether or not they see or experience ableism, right? It's always right there for them. And so, in the midst of the pandemic, they were able to do very important work of calling out ableism, but then also helping.

And I don't know that the rest of the world was listening well, but if we were listening, disabled persons were helping us to navigate this pandemic from all the wisdom they have. I think that's an example of, as I talk about in the book, how churches need to really listen to these voices of lament because they point to injustice; and calling out injustice is always a faithful thing to do—it's following Jesus towards something that looks more like justice.

We have to start with what's not working. And I think sometimes in the church we're like, “Oh, no, no, just don't say so much about that.” But I just could see this really prophetic, bold standing up against the sins of ableism on Twitter in a way that I didn't necessarily see in the church.

So, I invite churches—if they don't have disabled people in their pews—to find disabled activists, especially disability-justice activists because that's where the disabled people's movement goes. It goes toward a movement that's more hospitable to black and brown and queer people. And so, I invite churches to really listen to—to use your word—the “good” that is in this prophecy around our lives being undermined by ableism.

I just could see this really prophetic, bold standing up against the sins of ableism on Twitter in a way that I didn't necessarily see in the church.

But you know, your body will have experiences where you will be frustrated with something. Especially if you're lucky enough to grow old, you will be frustrated with things that your body cannot do or you'll be frustrated with mental health experiences.

I mean, so many of us have gone through that during the pandemic. You will have these experiences and I think you will look around and you will notice the way in which our culture is constantly reinforcing that, to be good, you have to be productive, right? You have to be on time. You have to be able to work. You have to be able to work like really hard and over time.

All these things that I feel are actually quite present in the Bible. In return, we are given the Sabbath, an appreciation for beauty, and a recognition that everybody has gifts. These start to kind of really clash with this culture that we've created for ourselves.

So, I think that there's so much wisdom in disability theology in terms of really interacting critically with that culture and leading us in a direction I think is healing and is about treating ourselves as whole people. I think this is living into the type of human flourishing that God wants.

One of the reasons I go towards this language of human flourishing is because Sharon Betcher, who is a disability theologian, talks about the way in which disabled people can flourish as well.

I think we have to proclaim a totally different vision of what it means to be the church and to do justice.

When we get into just talking about health, sometimes we start to come up with a narrative that, once again, excludes certain ways of being. The article that you wrote and your experience with your own body I think is really telling there. Because I don't believe, when we think about justice, God is imagining a future that you know only includes flourishing for those who have able bodied. But I worry that we do have that in our culture, so we really have to fight against that in our churches. And I think we also really have to proclaim a totally different vision of what it means to be the church and to do justice.

That's the hope that I have for the church: that we could be these pockets of resistance. When Trisha Hersey talks about, for instance, that rest saved her—that is knowledge that disabled people have, right? Like, they know this too.

So, I feel like there is this intersectional knowledge from the underside of our American society and culture. I think when you are able-bodied, you can kind of make yourself think, “I don't need that. I'm fine. I can do this all on my own.” And that is so antithetical to the gospel, right? There's so much goodness in walking with Jesus and disabled people are imagining a form of flourishing that really does include all of us.

A: The last question I had for you is about a small paragraph that you place in the introduction of the book that stuck with me as I was reading. It is about your daughter, Lucia, and how in her first few months of life there was no worry that she would receive love, but the question would be if she would be able to give love. You point to this being a fundamental aspect of our experience as humans—that reciprocal relationship. Looking back, even in the few times that I've met Lucia—like, she's just pure light; and clearly is constantly giving love to others.

But returning to what you’re highlighting in that story— I appreciate how you point to this reality that fundamental to us as humans is the ability to not only receive love but to give it. In relationship, this practice of loving is a way of being in the world and a practice of, not only flourishing ourselves, participating in their flourishing of others.

Could you talk a little bit more about love as a way of being in and relating to the world and also how this relates to ministry with and alongside disabled people?

E: Yeah. I mean, I think one of the things that I was trying to get across in that anecdote was a recognition of my own ableism. A lot of times when I tell people about that, they'll try to make me feel better. Like, “Oh, well that, you know, you just wanted her to be able to express love. That's not a bad thing.” But really what was happening was a failure of imagination on my part. Just because I couldn’t imagine how someone who doesn't have a lot of purposeful movement and doesn't have words and who can't eat by mouth could express love doesn't mean God can’t either. I think of that verse, “impossibly more than we can ask for or imagine,” (Ephesians 3:20).

An anthropologist, I love when I'm wrong about things. I learn more when I'm wrong about something. (I hope that I don't hurt anyone, of course, in the process when I'm wrong about something). But I think that this is a place where I hope that the book does this work of opening people up to ministry and leadership and ultimately how love looks different than they might have expected and expands their vision of the kingdom of God.

I share in the book some of the research that impacted me the most by some psychological researchers who studied people with autism and were talking about how it's really not autistic people that don't want to engage socially, it's non-autistic people. Because when a person who is autistic isn't making eye contact, the non-autistic person stops making eye contact and the whole communication shuts down. Right? They often literally walk away from the person. Meanwhile, for the person who has autism, maybe they are not looking straight at you so that they can engage with you. They're engaging with you in different ways and you're missing it. Sometimes it feels like a gigantic sort of messed up “love languages” situation.

I think about a lot of disability activists on Twitter but also folks who come into churches and are deeply frustrated with the ways that they've been left out and have a lot more vision in terms of how we could make space accessible or how we could make worship accessible.

And a lot of times they're just like brushed off as like, “oh my gosh, like you're so difficult and you're complaining and you're annoying.” I think, for these activists, this work is an expression of love— like nobody would interact with the church that way if they didn't care.

It breaks my heart when we miss these relational bids. We miss these ways in which we actually are showing up for each other for the Kingdom of God just because we're pretty unfamiliar with disability.

Do you mean to tell me that somebody can't lead because they can't see, or because they have bipolar, or because they are autistic? It leaves me speechless because my experience has been so wonderfully otherwise.

Going back to the idea of being able-bodied—we have certain ways that we prioritize when it comes to giving and receiving love. And so, I completely agree with you. I look at Lucia and I just don't understand how someone who can't move can light up a room. And she does! You know, you push her into the room in her wheelchair and she's beaming at everybody and smiling. We talk about how she smiles with her whole body—and she can't move her body much. I don't know how she does this. But, you know, that's really like not for me to worry about, right? That's for me to be able to receive and to wonder at. And so that's like really what I hope the book does is give enough kind of I call them glimmers of the Kingdom that people can trust and believe that God is working in and through the ministry and leadership of disabled people. This works to disabuse all of us of these kind of biases that we have—obviously when it comes to disability, but also even when it comes to something like love.

The other thing I would just think about is, if you think about someone who's loved you really well in your life, how did they do that? You know, was it that they did or said, or how did they express their love? And often it is ridiculously simple, right? Like, I mean, people aren't coming up with things like, “You know, when my fiancé proposed to me in front of the Eiffel Tower…”. No, people are thinking of, “Oh, you know, someone who sat with me when I was sad.”

And so, the idea that disabled people can't be ministers and leaders is such a failure of the imagination of human beings. Do you mean to tell me that my daughter can't sit with you when you're sad? I mean, she is incredibly gifted at that! She is such a comforter. So much so that I dedicated book to her, “a Supreme Companion.”

Do you mean to tell me that somebody can't lead because they can't see, or because they have bipolar, or because they are autistic? It leaves me speechless because my experience has been so wonderfully otherwise. As I said earlier, I just can't wait until these are the folks leading the church. Again, I think we just get hung up on these really narrow definitions, right of what it means to follow Jesus. And like I'm all for like blowing those out of the water. I think, and I hope that this book is a part of that process.

A: I think it will be in a wonderful way.