There is Thomas, the gumshoe.

Bracing himself with a hand on his hip as he inquisitively leans in for a closer inspection. He is confused, fearful, and doubting. Just a week ago he stated with confidence, “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.” (John 20:25).

Here stands his dear friend—a companion who now walks through walls and beyond gates of death. Neither entirely corporeal nor a translucent ghost, Jesus appears before Thomas in a liminal space between resurrection and ascension.

This resurrected body bears wounds—the scars of wrestling in this world.

“Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side,” Jesus comforts as he pulls away his robe revealing an open scar that once held the head of a centurion’s spear before pouring out blood and water.

“Do not doubt but believe.”

Now the disciples have gathered around. One stands with his mouth agape while another watches closely as Thomas lifts his right hand and inquisitively extends his index finger.

If Thomas is the lead detective, the disciples are all witnesses to the miracle looking for reassurance that this man is truly the Christ. They’ve given their statements and now await assurance that their own words are true.

Without warning, Jesus gently reaches for Thomas’ right hand and pulls it towards him, taking his scarred hand and guiding Thomas' finger into his lacerated side.

It is an unnatural intrusion of flesh meeting flesh. But, there is little natural about this situation in the first place.

There is no aggression, no anger, no hesitancy, no pain. Only the love and intimacy of the disciples and their beloved teacher.

Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God!”

In moments of chaos, Jesus reminds the Christian of their common life by offering a needed reorientation to the redemptive work of God in the world.

“Peace be with you,” Jesus says. John 20:19, 26

By re-entering the world in a resurrected body that bears the scars of the cross, Jesus offers us a renewed imagination of our place in society. Far from the escapism that pervades much of the church today, Jesus shows us our bodies might become the site of neighbor love and radical witness to the Gospel that go far beyond words.

In his treatment of The Divine Love, Friedrich Schleiermacher explains that self-giving love is essential to what and who God is.

This love, according to Schleiermacher, is “the impulse to unite self with neighbour.” Therefore, the divine manifestation of love is “the union of the Divine Essence with human nature” found in the person of Jesus Christ.

In other words, Jesus Christ is God’s pure act of love—of God’s uniting Godself with us.

At the location of Jesus Christ, God is united with humanity as creation perceives God in concrete form. In the incarnation of God, the constancy, perseverance, and persistence of God’s redemptive action are made clear. At the sensation of Jesus’ flesh, Thomas is led to Gospel proclamation. “Jesus is Lord.”

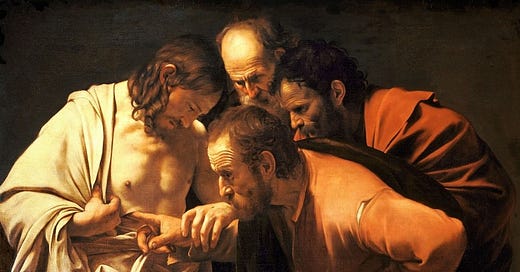

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s depiction of a doubting Thomas exemplifies Schleiermacher’s understanding of Divine Love. It is provocative and offensive—bringing the observer eye-level to the event shared between Jesus and Thomas.

Evoking a visceral response, Caravaggio envelops the scene in a warm but concentrated light. This illumination reveals a theological reality present in the Incredulity of Saint Thomas: Jesus is no longer drenched in the blood of the cross, but rather the disciples each are saturated in hues of a warm red. A divine exchange has occurred. The pure act of love has been accomplished. Grace is ours.

Placed together, Jesus' space-making action for Thomas’ hand offers Christians today a uniquely Christian conceptualization of the “common” and the “good” that leads us to a robust practice of neighbor love in the here and now.

As Oliver O’Donovan elucidates in Entering Into Rest, the “common” cannot be understood apart from that which is “communicated within community.” “There are as many common goods as there are communities,” he explains, “and as many communities as objects of communication.”

In emphasizing the communal and communicated, O’Donovan posits that language of “common good” can point backwards to the gift of community and forward to the City of God with aspirations of reception and imitation.

Christians might best lean into the dynamic word for fellowship in the New Testament: koinōnia. Paul uses this language both to describe the act of charity (Romans 15:26) and the church itself as the “community of the Holy Spirit” (2 Cor. 13:13). What is common among the people of God is a desire to be in relationship with Jesus Christ and to participate in his Spirit’s mission in the world.

Given that a community is a relation of relations—a reciprocal willingness to look to one’s left and right and say “these are my people”—and that language is always socially conditioned by place and time, we may conclude without question that the follower of Jesus has a distinct claim of what constitutes the “good” forged within that koinōnia of those united in Jesus Christ.

Once again, we may look to Jesus Christ to understand this.

Being perfectly conscious of God's divine will and action in the world, Jesus is continually moving towards the formation of fellowship and communion.

Christ is always making space for the “other” at his table and even for the spear of his enemy in his side. Rather than following the established Roman path of the cursus honorum (path of honor), Jesus moves towards the poor, the blind, the orphan, and the outcast to constitute a community marked by radical love.

Karl Barth explains in his commentary on the Phillipian Christ hymn that Jesus’ path to exaltation is paradoxically found through self-humiliation.

“Christ humbled himself — not, he was humbled,” Barth writes in a lyric of his own. “O infinite sublimity, of which it must be categorically true that there was none in heaven or earth in or in the abyss that could humble him! He humbled himself.”

Reflecting on Barth’s commentary Bruce McCormack adds in The Humility of the Eternal Son that “it is as the humiliated and obedient, that [Christ] is exalted…The ‘mystery’ of Christ’s deity...is the mystery of God’s readiness to participate in human nature.” This radical pursuit of God is an unbroken action of raising the believer from death and into life, orienting them in the chaos of life to God’s self.

The “good” for the Christian is that which follows in the example of Jesus’ hospitable, uniting, space-making work that gathers together those whom God has beckoned through a covenant of grace. Seeking the “good” is a deeply relational act of loving, joining, and, as Eric Gregory writes in Politics and the Order of Love, recognizing “the prior initiative of God’s gracious love in Christ.”

Too often today neighbor love is a utilitarian act. We practice neighbor love to exemplify our own virtue or goodness. Not wanting to be perceived as the parabolic priest or Levite, we look over our shoulder for a camera, audience, or reporter to serve as a witness to our good acts.

This disembodied Christian imagination is exemplified in Salvador Dalí’s 1954 piece Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus).

Christ’s body, while covered only in a loincloth, is healthy and composed. Christ bears no scars from the flogging whip, no holes from the crucifix nails, no crown of thorns mocking his kingship.

Christ is disconnected even from the cross itself which is portrayed by Dalí as a geometric hypercube hovering over a chessboard of barren landscape. Christ’s triumph over death is pragmatic and abstract. There is no urging for Thomas to place his hand in Jesus’ side because no such space exists.

The contrasting images of neighbor love here are clear. In order to follow Jesus’ example of perfect love, we must be willing to love radically in this world as embodied and temporal beings, living with and through the scars of the saeculum—the age between the cross and the Kingdom. In that unceasing action of redemption, our wounds are resurrected with Christ as they become an open channel for God to speak to the world.

Remembering Schleiermacher’s insistence that love is that Spirit-empowered impulse to unite self with neighbor through the love of God’s poured into our hearts (Romans 5:5), we ought to exemplify neighbor love as sacrificial compassion (Luke 10:37)—what Saint Augustine calls “misericordia.” This practice of mercy is, as Caravaggio depicts, the gentle hand of Jesus guiding Thomas’ finger into his side.

Our scars bear witness as we join ourselves with our neighbor. “Come and see what God has done!” we proclaim.

Confused, our neighbor may ask, “Has God inflicted these scars?”

“No,” we can confidently reply, “but God has seen me and healed me (2 Corinthians 5) because God, too, bears the scars of this world.”

The heavenly places are filled with a scarred people (Ephesians 2:6) who bear the marks of loving well in this world.

Christian love is not superficial and disconnected, reduced to abstract geometry and a woundless God. Christ-like love is embodied and costly, but it is the path to true life (Luke 10:28).

The renowned theologian Bruce McCormack once wisely remarked that the claim to be “Christian” is often aspirational. The life of love that we strive towards flows from our relationship with God; and apart from this intimacy, our attempts at neighbor love will always fall short. But often we find ourselves even after many many years, like Thomas drawn away from God. “I need to put my hand in his side,” I, the gumshoe, demand.

And, again, Jesus comes to us without hesitancy, gently guiding our hand to his side. “Taste and see,” Christ comforts as we receive the bread and wine, “because I am good.”

Once again, proximity to Christ reorients us to the theological reality of redemption in our chaotic world.

May we reply, “My Lord and my God!”