Last week was one of those weeks. My inboxes were filled to the technological brim, projects were due, meetings were scheduled, and evening plans were set.

Even through the hectic schedule, I was able to finish up a few articles:

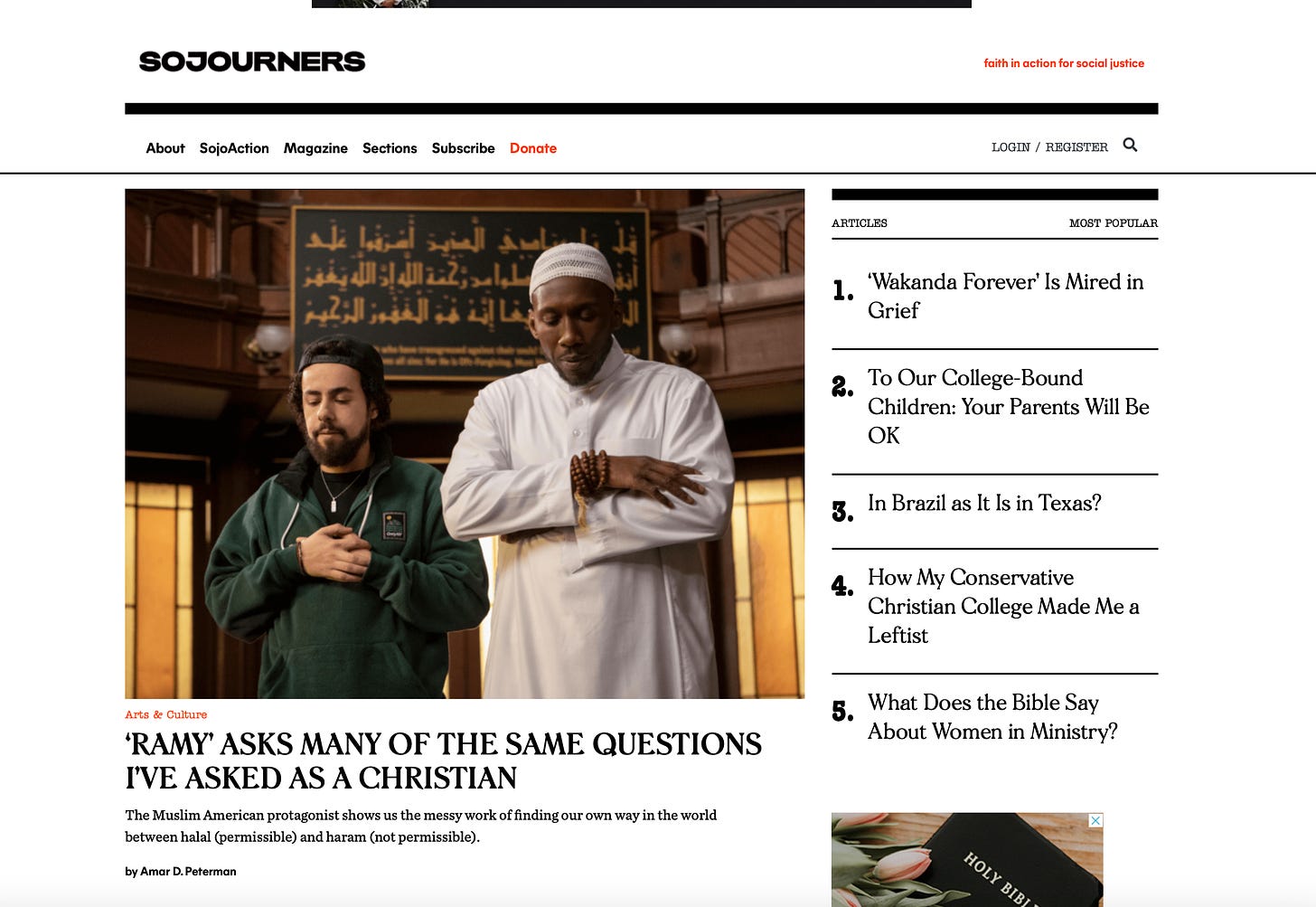

“‘Ramy’ Asks Many of the Same Questions I’ve Asked as a Christian” in Sojourners.

“There’s something about destiny that’s always felt hopeless. It’s like, no matter what I do, I’m just going to be where it was written for me to be … It's already been chosen, but we still have choice. It's a concept beyond our understanding. How can you choose what's already been chosen? Only God could know. Are we ever wrong or right?”

The italicized quote doesn’t come from a Christian pastor wrestling with predestination or a sermon about God and free will. It is an excerpt from the opening monologue of Ramy’s third season. Ramy is a Hulu series wrestling with deep questions of the Islamic faith. The show follows Ramy Hassan (Ramy Youssef), a 20-something son of Egyptian immigrants, as he navigates the tensions of dīn and dunyā — religion and the world. Transcending the clichés of blind religiosity, terrorist sympathies, and the social ignorance stereotypically associated with Arab and Muslim American life, Ramy shows us the messy work of finding our own way in the world between halal (permissible) and haram (not permissible).

“Throwing Our Own Potluck: A Conversation with Wajahat Ali” in Interfaith America Magazine

Wajahat Ali is a child of Pakistani immigrants, the father of three children, a columnist at “The Daily Beast,” the survivor of several near-death experiences, and a “recovering attorney.” He is also a brilliant writer and storyteller. His latest book, “Go Back to Where You Came From: And Other Helpful Recommendations on Becoming American,” proves all of this to be true.

Most importantly, though, Wajahat is a person of deep hope. Through trial and challenge, he continues to hold on to the possibility that we might recognize as humans that “we are all connected, even when we feel so distant and untethered to each other’s truths and realities.” The story of his latest book is one of the slow realization that people, even across a chasm of differences, “have the capacity for decency and kindness.”

Seated in Interfaith America’s Chicago office, I had the immense honor of conversing with Wajahat over Zoom. In the following conversation, we discuss many topics ranging from tokenism to potlucks filled with biryani to our experience as those who come from what a former president described as “s—hole” countries. Through it all, though, Wajahat affirmed two central truths: Goodness can be found in this world and it is our job to bring this goodness to light.

“How I Changed My Mind About Black Lives Matter” in Sojourners

“Oh Lord, not this again,” I thought. In the fall of 2015, I was sitting with my freshman peers on a worn-out, red upholstered seat in Moody Bible Institute’s Torrey-Gray auditorium. The president invited a Black preacher from the South Side of Chicago to the stage along with “Embrace,” the campus student group focused on creating a welcoming community for Black students. As they made their way to the stage, I gathered my belongings and prepared to leave. As soon as the pastor began to speak, I rose and turned up the aisle, only looking back once in a small act of self-righteous defiance. I hoped the speaker would catch my gaze and feel convicted over the heresy he preached. Pictures of Black Lives Matter protests scrolled across the screen, confirming in my mind that leaving was the right decision.

I came to Chicago as a bright-eyed and incredibly ignorant 18-year-old. To better understand the pressing issues of our society, I turned to clips from political commentators and conservative provocateurs Tomi Lahren, Ben Shapiro, and Matt Walsh on Facebook. They spoke passionately about a liberal movement hellbent on deceiving and dividing our nation, embedding Marxism into our democracy, and making everything about racism. The pinnacle of this not-so-hidden liberal agenda was the Black Lives Matter movement.

However, by 2016, my stack of “John” books — John Piper, John F. MacArthur, John Winthrop — that occupied my bookshelf were replaced by a new collection of “James” books — Willie James Jennings, James H. Cone, and James Baldwin. By 2017, I was writing essays on a “post-colonial” reading of Romans and challenging the whitewashing of Christianity in my undergraduate courses. By 2018, I was speaking on public panels about the necessity of the Black Lives Matter movement and MacArthur’s erroneous statements regarding “Social Justice and the Gospel.” Just a month before graduation in the spring of 2019, I sat in the front row of Torrey-Gray auditorium as Jennings presented an honorary lecture on the importance of land and place in theology. I did not make an early exit this time.

This week, I am incredibly grateful for all of you. I launched this newsletter earlier this year with great hope for what it could be. You’ve all played a part in making this platform what it is. As Twitter comes crashing down, I am excited to continue investing in this newsletter. I’d love for you to join me.