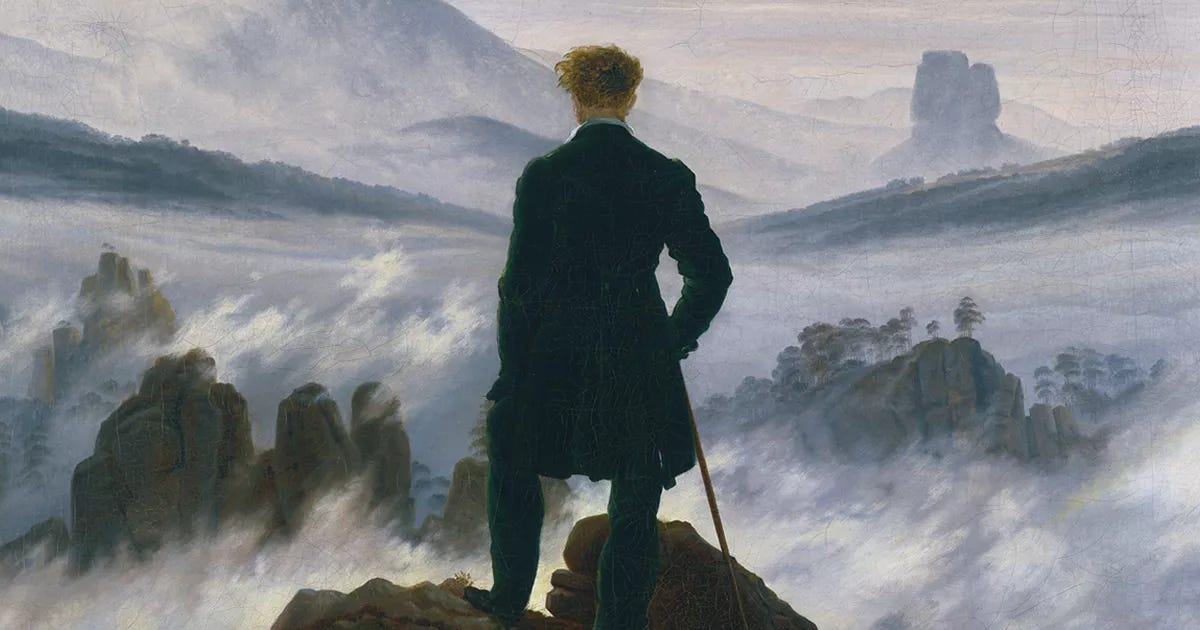

worldview, imagination, and the fragments we hold together

we see but in glimpses, taste but in bites, smell but in wafts, and hear but in echoes reverberating through space far greater than we can comprehend

“Worldview” is language familiar to the church. In response to the events of our world, Christians often contrast an upstanding “biblical worldview” with a morally depraved secular outlook. This worldview, in return, provides the context in which we place our theology, interpretations, and practices, creating a consistent logic that justifies what we believe and why we can believe it. In other words, our “Christian worldview” reaffirms the truths we hold through the stories we tell about ourselves and others.

“Worldview,” however, is not a term that comes from the Christian tradition. It is a secular modern term (Weltanschauung) authored by Immanuel Kant who boldly argued that through our empirical knowledge—what we experience with our senses and materially engage with—we may rightly perceive the world and organize it accordingly.

When we appeal to a worldview, we tie perception to order: to see a thing is to claim it, and to claim a thing is to assert possession over and against it. But can we possess the whole world?

The Christians who claim we can achieve such a possession have used their faith to incredibly destructive and dehumanizing ends—ordering the world by gender, race, and class, normalizing such hierarchies as universal, and measuring Christian faithfulness according to it.

The reality, however, is that no person possesses a true worldview because no individual can fulfill its foundational claim—that our empirical knowledge leads us to rightly perceive and order anything at all. We are mortal and our existence is ephemeral. We are not God.

What, then, do we have? How do we make claims of the world around us if we don’t have a worldview?

I believe that what we see through are not worldviews but rich and vibrant imaginations. To imagine, as Willie Jennings writes, is to recognize that what we hold are fragments.

We see but in glimpses, taste but in bites, smell but in wafts, and hear but in echoes reverberating through space far greater than we can comprehend. Rather than claiming our experience as universal, the work of imagination requires us to pick up these fragments we hold loosely and seek to make sense of them in community. In this process, our fragments are brought to a shared table where others bring the pieces of glass, metal, cloth, and stone they have found along the Way. In community, we are guided by the Holy Spirit as we piece together our stories, experiences, traditions, histories, fears, and loves.

Fragments, of course, leave open the gray, in-between space of finitude. These materials do not perfectly match. This leads to a central work of imagination: formation.

Imagination is a process of formation. The question we must ask ourselves is this: What are we being formed towards? To imagine is to create and dream together of new ways of being in and relating to the world. Imagination is drawn from a mythic fabric used to create new stories, put them on a page or a screen for all to see, and watch the world change before our eyes.

As Karen Swallow Prior writes: “The imagination shapes us and our world more than any other human power or ability. Communities, societies, movements, and yes, religions are formed and fueled by the power of the imagination.”

Imagination holds the potential to recognize the beauty of the fragments that form us into more loving, empathic, just, and hospitable people. The creative work of imagining together is a compelling and beautiful witness to the Gospel of Christ in our world today that does not prescribe a vision, but rather invites others to participate in a story still being told.