wonder is a prescription for our soul’s yearnings

"God is the poetry caught in any religion, caught, not imprisoned. Caught as in a mirror that he attracted, being in the world as poetry is in the poem, a law against its closure."

When Emily and I first started dating, we often spent hours at the Chicago Art Institute looking at countless paintings. In each room, Emily would glance around, taking in the room before moving towards one painting. Standing several feet back, she’d stare at it inquisitively, examining every stroke, shadow, and color.

I took a different approach. Instead of focusing on a single piece that caught my attention, I’d make my way around the room reading all of the small informational squares underneath each painting. At each one, I’d take a picture so I could go back and research more later. I appreciated the painting, but I wanted answers—I wanted to know what the artist was trying to say. I’d find time for “awe” once I had my answers.1

…

Wonder has never come easy to me.

For much of my life, I approached the Christian faith in a similar manner to my excursions to the museum—glancing up at God’s redemptive work around me and then placing it into my systematized, compartmentalized theologies. I’d read a piece of scripture, say a quick prayer, and then run to the library, grabbing commentaries and concordances off the shelf. Yes, I saw the picture God was painting, but my concern was finding the answers within and behind it.

I soon found that this disenchanted, knowledge-driven, faith was a cumbersome and unfulfilling one. Seeking knowledge as an end in itself only bent me further inward and led me down rabbit trails of obscure questions. I read endlessly but grew little in love for God and my neighbor. So quick to run to answers, I missed the beautiful tapestry of divine action all around me. I couldn’t appreciate the painting simply because it was, I needed answers.

the christian life isn’t an exam. it’s an essay.

…

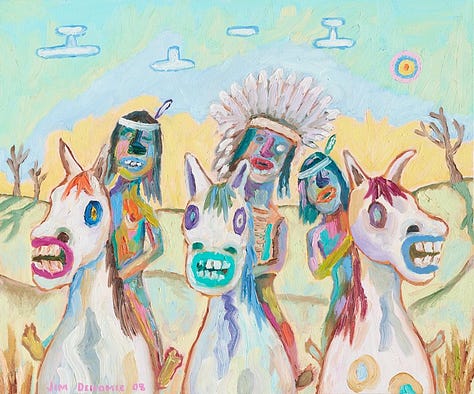

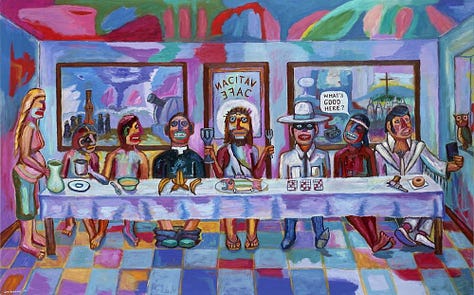

While in Minneapolis this past weekend for a collaborative book project, I met up with my good friend Luke who suggested we visit the Minneapolis Art Institute (The Mia). We chatted and wandered through a collection of artifacts, sculptures, and paintings created and inspired by the indigenous Ojibwe, Lakota, Anishinaabe, and Dakota communities who continue to inhabit this land. We ended up in a gallery filled with paintings by the late Ojibwe artist, Jim Denomie.

If you are not familiar, Denomie’s paintings are something to behold. Sometimes encompassing an entire museum wall, Denomie did not shy away from the gruesome, profane, and horrific. It is haunting art. At once, your mind is racing with thoughts and yet there are no words to speak. It is the kind of art that makes for a dead-silent gallery.

As we journeyed through the gallery, I still desired to know what each piece meant and felt the impulse to grab my phone and snap a picture for later study. However, what came to mind in these moments was a question found in a Walt Whitman poem I read recently titled “Song of Myself:”

“Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?”

What Whitman is getting at in the poem, I think, is that the pride of understanding is simply another form of ignorance.

Thinking of Witman’s question, my phone remained in my pocket.

I appreciated the art simply because it was there and I was there, standing before it. The goodness of the moment did not demand the accumulation of knowledge, but simply the willingness to exist.

…

Early in my Christian faith, I was so proud to feel I had the single, universal answer to the deepest questions of our world. I had the method, the theory, and the skill to discern absolute truth. I was proud to be right.

Of course, I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Christian Wiman, reflecting on Witman’s question, offers a powerful response of his own:

Have you felt proud to know the meaning of scripture, the right kind of theology, to know what you believe, or even, perhaps, that you don’t believe in anything at all? Perhaps you have forgotten the law against closure. By all means, let us declare our faith, if we have any; let us be “God’s trumpets.” Because in that first Amichai poem it is not only “doubts” that dig up the yard and restore the ruined house, but “loves” as well, and love is decidedly active and declares itself. But let us also keep in mind the ineluctable law against closure, the poetry of reality.

…

Almost a decade removed from my first trip to the Chicago Art Institute, I am still learning to lean into wonder. Gradually, my clenched fists around knowledge and certainty are loosening, making space for mystery and unknowing.

And, in each day of this process, I find myself increasingly inclined toward love, hospitality, generosity, kindness, forgiveness, and gratitude.

This, I am increasingly convinced, is what our souls yearn for: beauty, not certainty; wonder, not absolutes.

You can't pray a lie, said Huckleberry Finn;

you can't poe one either. It is the same mirror:

mobile, glancing, we call it poetry,

fixed centrally, we call it a religion,

and God is the poetry caught in any religion,

caught, not imprisoned. Caught as in a mirror

that he attracted, being in the world as poetry

is in the poem, a law against its closure.- Les Murray, “Poetry and Religion”

Reading:

Ashish Varma, “Even in the Dark: Finding the Rest and Grace of Jesus on Diwali” (

)“Overshare: Or, I wonder if I'm getting this wrong” (

)Hanna Reichel, “After Method: Queer Grace, Conceptual Design, and the Possibility of Theology” (WJK, 2023)

Watching:

Khabi Khushi Khabi Gham (Netflix)

Invincible - Season 2 (Prime Video)

Listening:

For those interested,

has two wonderful reflections on visiting museums that are well worth your time: “How to fall in love at a museum” (Quid Amo) and “How to Visit a Museum: Disciplines of Availability” (Image Journal)

Welcome to the Christian Wiman fan club, Amar 🙌🏽